The solidbody shorties appeared very early on in Rickenbacker history—way back in 1957, before most of the line as we know it today existed. The 900, 950, and 1000 were no frills short scale (20.5”) guitars designed for “the ladies” and young students with smaller hands, and were often sold as a package with M-8 amplifiers. Fender had entered the short-scale/student market in 1956 with the 22.5” scale Musicmaster and Duo-Sonic as had Gibson with a 22.5” scale Les Paul Junior, so it must have looked like a market worth chasing. In hindsight…?

There are two main difficulties in researching these guitars today. The first is that there just aren’t that many of them out there—these were never high volume guitars. And the second—which compounds the first!—is that many people can’t tell the difference between the 900 and the early 1000. Consequently the register and the internet at large is littered with misidentified guitars. But it’s remarkably easy to spot the differences when you see them side by side, so let’s start there.

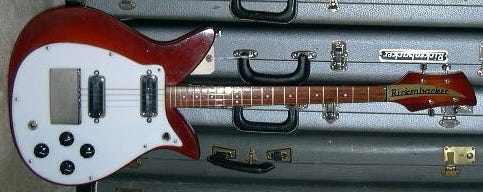

So here’s what they looked like in 1957, their first year of production:

Hey wait…there's four guitars there! Yes there are. There are two distinct “year 1” versions of the 1000, and that’s the key driver of the confusion. But let’s see if we can make it easy.

What are the key differences between these three models that you should be able to easily spot? For the 900 and 950 it’s the number of pickups—1 for the 900 and 2 for the 950–and the control layout—2 knobs (volume/tone) and 1 switch (tone circuits like a Fender Esquire) for the 900, and three knobs (volume/tone/rotary pickup selector) for the 950). If you can’t tell the difference between those two, well that’s on you.

It’s the single pickup equipped 900 and the 1000 that folks tend to stumble over—and for good reason—but there is one key difference that anyone can spot: the number of frets. There are 21 on the 900/950, and 18 on the 1000. All years, all iterations, that’s a constant. If you’re not sure what it is…count the frets and there’s your answer.

Now let’s look at the cutaways on all four guitars. The upper, large convex “tulip” cutaway is the same on all of them. But there are three different lower cutaways. The 900 and 950 got the same small slightly convex one, and it’s unique to those two models. The first 1000 got the same lower convex cutaway found on the “full tulip” Combo 400. But Roger Rossmeisl sure liked to mess around with stuff, and it didn’t take long—like a matter of months—for the 1000 to gain the far more functional lower cutaway we see on the final guitar that would carry over to the future 400 and 600 lines.

So that’s the other point of differentiation: “full tulip” or “half tulip”. Full tulip guitars have 2 convex cutaways, half tulip have 1 convex and 1 concave. The 900 and 950 is always a full tulip and, apart from the very first few months of production the 1000 is a half-tulip. Well…for a while, but we’ll get to that later.

So are we clear about how they’re different? Now let’s talk about what they have in common. You’ll note two different pickups, but that’s just a question of timing—these guitars launched right around the time Rickenbacker was transitioning from the DeArmond pickup made by Rowe Industries (click HERE to learn more about “other” Rickenbacker pickups) they’d first used for the Combo 400 to their own in-house design, the toaster.

So the first few shorties wore the DeArmonds, but it didn’t take long to transition to toasters. So ignore the pickups, that’s a red herring.

All three models featured neck-through construction, with the through neck clear coated and the slab body wings painted Jet Black (the Jetglo name wouldn’t appear until 1967). Jet Black would be the only color until 1959. The through necks feature dot inlays—with only 1 dot at the 12th fret and stopping at the 15th on both the 18 and 21 fret models. And then there’s the truss rod cover.

Often referred to as the “aluminum foil” truss rod covers, these were made of a thin embossed metal (a good bit thicker than aluminum foil, but not so thick they don’t dent easily!) with a black wash. Utterly unlike any truss rod cover before or since, it also appeared on the 425 at its launch in 1958 solidifying its role as a student/entry level signifier.

Keeping with the “no frills” theme, the tuners were white button Kluson deluxes with no bushings. Knobs seen to be whatever was handy in the parts bin with both KK “vintage” knobs and lap steel UFO knobs appearing. And then there’s the bridge:

Yup. Every bit of that is correct. What we have here is a lap steel nut resting in an undrilled standard bridge cradle held up by flathead machine screws. You ever wonder what the opposite of “spare no expense” is? You’re looking at it!

“But where’s the serial number?”, you ask. Flip the guitar over, and you’ll find it stamped into the bottom of the through neck, obviously.

So there’s no strap button there, so the guitar must have a saxophone ring like the Combo 400. Why didn’t they stamp the number there like on the 400? Because there is no ring! Just a cavity with a hook in it. Spare no expense!

And then there’s the backplate. I have never found a convincing answer as to why early Rickenbackers have these backplates. On the Combo 600 and 800 sure—the guitar is carved out from the rear and you gotta cover that up. Fine. But on the solidbodies? There are two explanations you’ll find that KINDA make sense.

One: it’s to better keep the guitar in place when you’re playing it. Remember, these early guitars had saxophone rings ONLY when new, so with only one point of contact between the guitar and the strap it’s going to move around. Take both hands off the guitar and you’ll really see what neck dive looks like! This explanation makes more sense for the Combo 400, which had a “flocked” backing with some texture to it—not the smoother ones you usually see on the early shorties and 425s.

Two: It’s a back protector to avoid messing up the finish, like the snap on pads you find on some later Gretsches and Voxes. I don’t buy that one. These guitars were designed in an era when guitars were worn a lot higher—and what’s more, these were student guitars which are usually played…seated.

We’ll probably never know. And you may also ask, “why do these protectors vary so much from guitar to guitar?”, because they do. You can find pickguards as back protectors on some of them! My best answer there is to remind you that these guitars were all basically hand made. They used what was handy or what “worked”…even if we don’t know the purpose today!

Ok. We’ve said about all there is to say about these 1957 guitars—and yes, we hadn’t gotten out of 1957 yet! Don’t worry, the rest will go faster.

Now look, if I’m being honest here there just aren’t enough examples out there to give you a definitive timeline of changes that occurred between 1958-1963. In 1959 we got more colors than just Jet Black, and they were “full body” colors with the neck now matching the rest of the guitar. Around that time we lost the back plate, and in 1960 we got a major upgrade in the form of a proper 6-saddle adjustable bridge—with the serial number . As far as the sax ring goes…sometimes it’s there, and sometimes it’s not?

Look, I don’t know how many times I have to say this: there are no absolutes when it comes to Rickenbacker—especially during these early days. Features come and go only to reappear and disappear again. So you WILL find exceptions to almost everything I say here. But these are rules that the exceptions will apply to. And that “anything goes” environment leads to things like this:

A tenor 950? Sure, why not?

Things began to calm down and standardize in late 1962/early 1963 so that by late 1963 the instruments had more or less reached their “final form.” Well, with one exception we’ll talk about in a minute.

When compared to the original 1957 instrument, the 1963-on 900 body went from a slab shape to more contoured, especially on the top edge. The pickup moved closer to the bridge. The bridge itself took a step backwards from the interim standard 6-saddle unit to a one piece compensated floating unit on a shorter bridgeplate—which now carried the serial number.

The white plastic button Kluson Deluxe tuners got small bushings, and the truss rod cover was the same white backpainted plexiglass unit all other Rickenbackers wore. The 900 would stay on the price list through 1979, but I’ve never seen one made after 1967.

The 950, with its two pickups, saw all the same changes as the 900 plus one more: the wiring changed to the standard 4 knob/1 switch layout instead of the odd 3 knob—with the third being a rotary position selector—layout it began life with. Also like the 900, the 950 remained on the pricelist through 1979, but 1971 is the latest entry on the register.

The 1000 saw all the same changes. But its evolution was not complete. In 1963 the model was pressed into use as a private label guitar for music schools—harkening back to its origins as part of a package deal for students along with an amplifier.

Renamed the ES-16 for this private label market, the guitar got a unique truss rod cover—branded “Ryder” for the Ryder Music School or “Electro” for customers who didn’t want/need their own branding.

In 1964 the guitar was redesigned—losing the convex “tulip” curve of its upper cutaway and changing to less expensive set neck construction. This would be its final evolution.

1000 production would end in 1966–although it remained on the pricelist until 1970–with ES-16 production ending a year later in 1967.

Except for the 1983 batch. 1983? I’ve heard it said there were a batch of leftover bodies—which is neither impossible nor frankly improbable—that the factory decided to build out. True or not, a batch of these were produced in 1983 with period appointments—Grover Rotomatic tuners, a Higain pickup, and the longer bridgeplate currently in use on the 450. Is that the REAL reason these exist? Your guess is as good as mine.

And that’s all there is to know about the student shorties. What I’ll say about them—as an owner of several in the past—is that they’re just fun to play. The short scale makes those crazy jazz chords easier to reach, and they make you think very differently about how you play. You do want a heavy string gauge though—12’s at least—to help with tuning stability. They’re a great way to get into a vintage Rickenbacker cheap, and a blast to play. Hooray for the shorties!